Get clear on what a UBO is and why identifying ownership is vital to compliance and due diligence

Who or What Is the UBO? (Definition + FATF Criteria)

Uncovering and prosecuting financial crime is hugely problematic, as money laundering and fraud schemes often involve the development of hugely complex corporate structures, across many borders and legal jurisdictions, designed to bury and protect the assets and details of the ‘mastermind’, or Ultimate Beneficial Owner (UBO). For compliance professionals, the work begins with unravelling the conglomeration and following the money to determine the person(s) behind it all.

In simple terms, the Ultimate Beneficial Owner is the person(s) with the power to control an entity. The UBO is further defined by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

The FATF is an intergovernmental organization founded in 1987 on the directive of the G7. Also known by its French name, Groupe d’action Financière (GAFI), it was initially formed to combat money laundering and other related threats. This mandate was expanded in 2001 to include terrorism financing.

The FATF has developed 40 recommendations designed to assist countries in battling financial crime. As of April 2022, it is reported that 76% of countries have now satisfactorily implemented all 40 recommendations, with 206 jurisdictions passing new laws and regulations to strengthen their compliance with the FATF.

In its Guidance on Transparency and Beneficial Ownership, the FATF defines UBO as “the natural person(s) who ultimately owns or controls a customer and/or the natural person on whose behalf a transaction is being conducted. It also includes those persons who exercise ultimate effective control over a legal person or arrangement.”

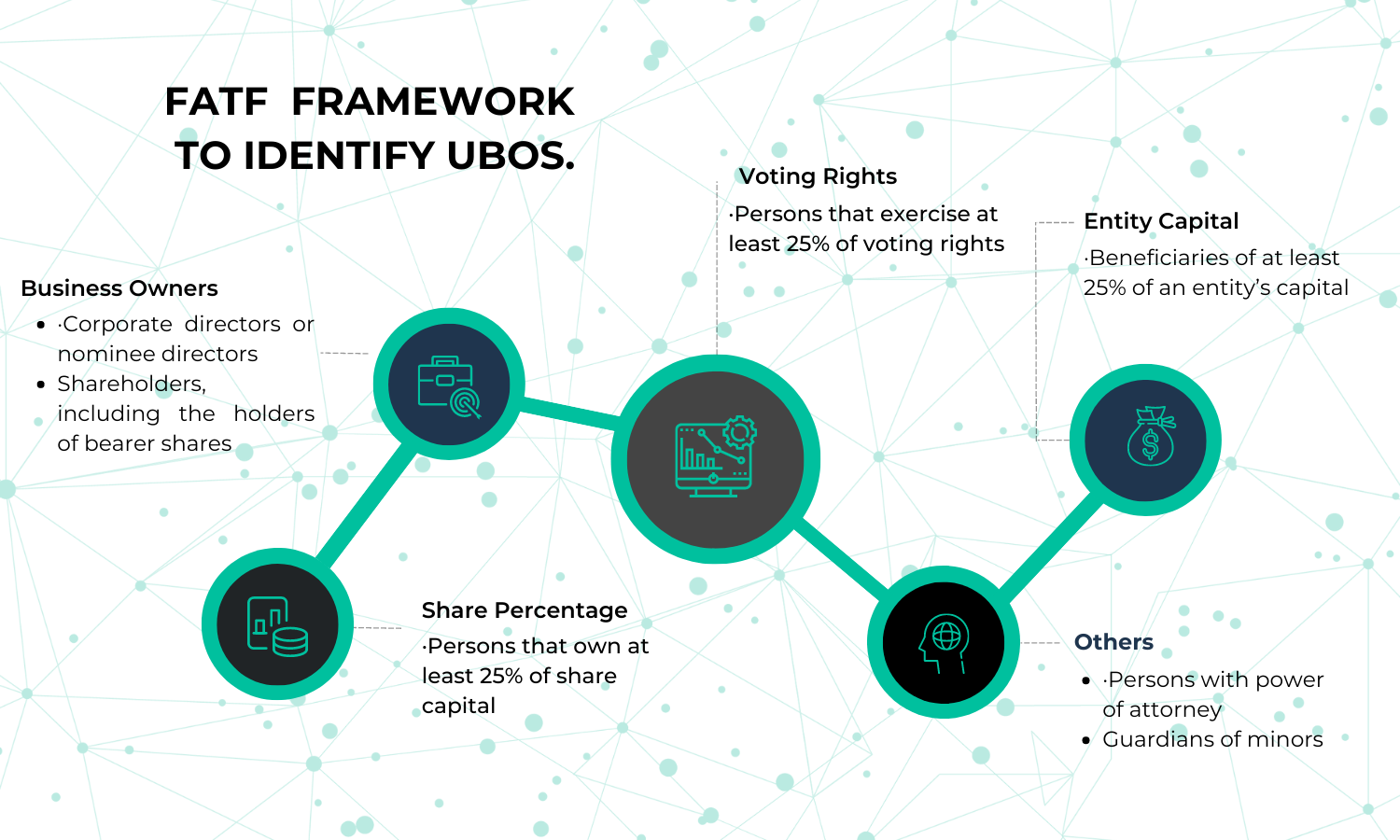

FATF has set out a framework to identify UBOs. This includes the following:

- Persons that own at least 25% of share capital

- Persons that exercise at least 25% of voting rights

- Beneficiaries of at least 25% of an entity’s capital

- Persons with power of attorney

- Guardians of minors

- Corporate directors or nominee directors that are appointed to conceal the true owners of a given firm

- Shareholders, including the holders of bearer shares that may be transferred anonymously

- A critical element of the FATF definition is that it focuses on the natural person. That is, it extends beyond legal ownership and control and takes into account the ‘ultimate owner’, being the person who exerts effective control.

The FATF provides examples of natural persons as persons who may exert ultimate control by means of their relationships, through historical or contractual associations or by exerting executive control over the daily or regular affairs of the legal person eg CEO, CFO, MD or President.

Historically it has been very challenging to determine the UBO. Even when possible to do so, investigations and paper reporting can take weeks, even months, giving fraudsters ample time to reconfigure their arrangements, staying one step (or more) ahead of being caught.

The Role of Financial Crime in Hidden Ownership

In a globalized economy with varying jurisdictional regimes, there are a myriad of opportunities for international crime syndicates to establish complex corporate vehicles designed to disguise themselves and enable them to carry on unlawful activities undetected.

While recent advancements in technology have sped up the way in which we communicate and do business, these same advancements have created more efficient avenues for sophisticated criminals to facilitate money laundering and fraudulent transactions.

So, the question becomes, how do you really know who you’re doing business with?

The Cost of Non-Compliance with FinCrime Regulations

It’s easy to think of financial crime, or so-called “white-collar crime”, as victim-less, where the offence only happens on paper, or impacts rich people who won’t notice, or multi-national companies who can ostensibly afford the loss.

The sad fact is, in the majority of cases, this couldn’t be further from the truth. The money that is exchanged in criminal transactions has to originate from somewhere, often at the expense of the most disadvantaged and disenfranchised people in the world. It is funded by drug wars in South America and human trafficking in third world countries. It’s a result of child labour in Asia and forced prostitution rings in Eastern Europe.

The proceeds are often used to fund terrorism or illegal arms dealings, or to line the pockets of the masterminds behind the schemes or activities. Often, by the time the funds are laundered around the globe, they are wiped clean of any trace of their malevolent origins. For professionals involved in ensuring good governance, the rationale is more than purely altruistic. There are also significant financial repercussions to consider.

The cost of non-compliance with financial crime regulations does not come cheap, and around the world governments are legislating to make the stakes higher than ever; particularly as they relate to anti-money laundering (AML), Know your Business (KYB), Know Your Customer (KYC), data privacy and MiFID (Markets in Financial Instruments Directive) regulations.

According to research conducted by Fenergo, a provider of client software for the financial services industry, and data from the World Economic Forum, an estimated $46.4 billion in enforcement actions has been levied against financial institutions and individuals since 2008.1

These penalties were bolstered by a $2.9B penalty to Goldman Sachs over the 1Malaysia Berhad scandal (1MDB) resulting in a record $10.4B total fines levied in 2020.

A Real-World Example:”The Asian Great Gatsby”

Considered one of the world’s largest financial scandals, the 1MDB conspiracy involved the embezzlement of a Malaysian Sovereign Wealth Fund by members of the Government and their affiliates.

The then Prime Minister, Najib Razak, was accused in 2015 of channelling approximately $USD700M into his own bank account, effectively robbing the Malaysian people. The charges were initially dismissed but later retried, with Razak sentenced to twelve years imprisonment on seven charges. It has been alleged by US prosecutors that a total of $USD4.5B in total was misappropriated, while only a quarter of that amount has been recovered.

The mastermind behind the scheme was identified as Jho Low, a Malaysian fugitive and former financier, who is now thought to be residing in China. He was reportedly instrumental in establishing the Malaysian sovereign fund and is said to be the beneficiary of multiple trust assets originating from the 1MDB fund. Previously known as the Asian Great Gatsby, Low partied with Leonardo di Caprio and dated Miranda Kerr, and is now the subject of a new TV documentary detailing the saga.

Strengthening Your UBO Processes

Despite the ostensible magnitude of the fines imposed on financial institutions, they are a mere fraction of the estimated proceeds of financial crime throughout the world, which is counted in the trillions.

Of course, understanding the UBO is not all about discovering criminal activity. Sometimes it is just a matter of knowing who you are really dealing with and understanding who the parties are within a given transaction or business arrangement. Whatever the reason, leading-edge technology is helping to speed things up.

Book a 15-min demo and see how AsiaVerify accelerates onboarding, reduces false positives, and keeps you audit-ready.